|

|

|

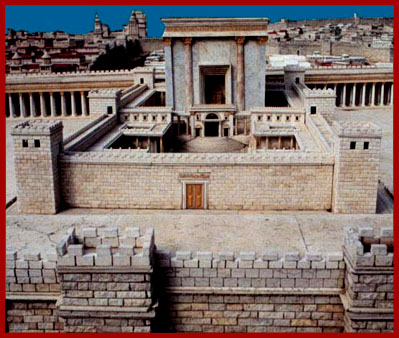

The Temple of

Herod

(Model-reconstruction) |

The Arch of Titus,

Rome, 180.

|

JEWISH

CAPTIVITY

and

REBELLIONS

|

|

|

AT THE

TIME of CHRIST

|

[...following a] violent anti-Jewish persecution (AD

38),. the Jews of Alexandria, In protest ,finally sent a legation to the emperor

in AD 40 to plead their cause. A noted member of it was the philosopher, Philo,

but the emissaries had little success (Ant. 18.8,

i

§ 257; Philo, Embassy to Gaius). When

Herod Antipas was exiled in 39, his territory (Galilee and Perea) was added to the domain of Herod

Agrippa

I. The latter, who had been insulted by the

Roniart prefect of Egypt, was more successful in influencing the legate of

Syria, P. Petronius, who had been sent out by Caligula in 39. King Herod urged

him not to press the issue of emperor worship; consequently, Petronius delayed

as far as Jerusalem was concerned. But when the pagan inhabitants of the coastal

town Janinia erected a crude altar to the emperor, it was torn down by the Jews

of the locale. The incident was reported to the emperor, who retaliated by

ordering the immediate erection of a colossal statue of himself in the Jerusalem

Temple (Philo, Embassy to Gaius 30 § 203). But Petronius still

procrastinated, while trying to get the Jewish leaders to accept this order with

good grace. Horrified, the Jews gathered in Ptolemais where Petronius was

quartered, and begged him not to erect the statue. Petronius wrote to Caligula,

only to bring down imperial wrath on his own head. Then Herod

Agrippa

visited Caligula in the hope of having him

rescind the order. Incensed at Petronius, the emperor commanded him to commit

suicide. However, the whole issue was resolved by the murder of Caligula on 24

January AD 41

When Claudius (41-54) came to the throne by the

acclamation of the Roman troops, his reign began with an edict of toleration in

favor of the Jews (Ant. 19.5, 2-3 § 279ff ). He rewarded Herod

Agrippa

I for his support of the Roman rule, extending

his territory to include that of the ethnarchy of Archelaus (Judea, Samaria,

Idumea), so that from then until his death he ruled over a territory almost as

vast as that of Herod the Great. Herod

Agrippa

undertook to build Jerusalem’s “third north

wall,” which, if completed, would have made the city impregnable. But before it

could be finished, Claudius who had been warned by Maurus, thelegate of Syria,

forbade any further work on it (Ant. 19.7, 2 § 326-27). [...] Herod

Agrippa

was an insignificant but pious king, whose

passing was mourned by the people, for at home he supported Pharisaism, even

though abroad he liberally advocated Hellenistic culture and contributed inuch

to the pagan institutions of Berytus [modern Beirut]. Given his support of

Pharisaism, however, it is not surprising that he persecuted the nascent Christian Church (Acts 12:1-19); one of his victims was James, the son of

Zebedee, beheaded ca. AD 44. Herod

Agrippa

died suddenly at Caesarea in AD 44, while attending the Vicennalia, games in honor of the

emperor (Acts 12:20 23 ; Ant. 19.8, 2 § 343-50)

|

Spread of the Christian Church.

|

On the death of Herod

Agrippa

I, the Emperor Claudius The primitive

Christian community became more and more conscious of its comission to

proclaim the “gospel of Jesus Christ” (Mk i:r). After some

initial success in converting Palestinian Jews (Acts 2:47; 6:7; etc.), the

apostolic preachers turned to the metropolitan centers of the Roman Empire.

Gradually the “good news” spread from Jerusalem to “the end of the earth” (Acts

1:18), addressed first of all to the Jews of the Diaspora and then to the

Gentiles.

Possibly it was in AD 36, when P.

Pilate was sent back to Rome and a new prefect Marcellus was named (36-37),

that the “great persecution of the church” (Acts 8:1) took place. The

appointment of a new governor seems to have been particularly apt for such an

outbreak. At any rate, it was in the context of a Jewish persecution of the

young Palestinian Christian community that Stephen was martyred and

Saul

of Tarsus “breathed [his] murderous threats”

(Acts 9:1-2). Saul’s conversion, which cannot be dated accurately, is plausibly

related to this time (-. Life of Paul, 46:16).

|

Herod Agrippa I (37-44).

|

The Emperor Tiberius died on 16 March AD 37. The

legate of Syria, L. Vitellius, was still in Jerusalein, trying to soothe the

feelings of the Palestinian Jews who had been outraged by Pilate, when the news

reached there of the new eniperor, Gaius Caligula (37-41). The Jews were the

first of the nationalities of Syria to pledge their allegiance to the new

emperor and hailed his regime, which was peaceful and quiet for the first 18

inonths. But whereas Tiberius had eschewed emperor worship, Caligula now began

to insist on it. He wanted images of himself as divus erected in all

shrines and temples (including synagogues) in the empire.

Caligula was not long on the imperial throne

before he conferred on his friend Herod

Agrippa

I, the brother of Herodias and the grandson of

Herod the Great, the territory of Philip’s tetrarchy in N Transjordan (-. 141

above). With this grant went the title of king. On his way back to Palestine,

King Herod stopped at Alexandria, and his brief sojourn there became the

occasion of a serious defamatory outburst against hini and against the local

once again reorganized the country into a Roman province to be ruled by

procurators. The last of the Herodian family to enjoy partial rule in the area,

however, was Marcus Julius

Agrippa

II, the son of Herod

Agrippa

I, who like most of his family had been brought

up at Rome and was a mere boy of 17 when his father died. He did not inherit his

father’s realm immediately, but when his uncle, Herod of Chalcis, died (48), he

became the ruler of this small territory on the slopes of the Antilebanon. He

subsequently relinquished this realm (ca. 52) and received from Claudius the old

tetrarchy of Philip, to which

Nero later added parts of Galilee and Perea. His relations with his sister Bernice (probably incestuous)

caused scandal in Rome (Ant.

20.7, 3 § 145; Juvenal, Sat.

6.156fî.). It was before

Agrippa and Bernice that the prisoner Paul

had to explain his case in Caesarea (Acts 25:23fî.). After the fall of

Jerusalem, Agrippa

II went to Rome and lived there with Bernice; he

was a praetor for a while and died between 93 and too. While ruling in

Palestine, he had little influence on the Jewish population; he was opposed

constantly by the priests and arbitrarily nominated and deposed high priests in

rapid succession. The end of the Herodian dynasty was not glorious.

In

this period, and more precisely in the procuratorship of Tiberius

Julius

Alexander (46-48), Judea and other parts of the

eastern Mediterranean world suffered from a severe famine. A prediction that it

would affect “the whole world” is recorded in Acts 11:28. The striken

Palestinian populace was aided by grain brought from Egypt with the help of a

Jewish convert, Queen Helen of Adiabene (Ant.

20.5, 2 § 100-101). Possibly this

famine was the occasion of the visit of Barnabas and

Saul

to Jerusalem (Acts 11:29-30; 12:25;

-> Life of Paul, 46:5, 24). It was possibly in the summer of 49-the date cannot

be determined precisely (-. Life of Paul, 46:28-34)-that the meeting of

the apostles and elders took place in Jerusalem. The Jerusalem “Council” decided

against the circumcision of Gentile Christians and their obligation to observe

the Mosaic Law (Acts 15:2-12). It was the historic decision that emancipated the

Christian Church from its Jewish origins.

The

true rulers of Palestine in this period were the procurators, who made no

attempt to understand the Jewish people, made little allowance for popular

manifestations, and rather looked for the chance to harass them. The period was

marked by a succession of minor uprisings (Ant.

20.5, 1 § 97-98; 20.5, 3 § 106-12;

HE 2.11, 2-3). The most notorious procurator of this period was M. •Antonius

Felix

(ca. 52-60), who married into the Herodian

family, becoming the second husband of Drusilla, the sister of

Agrippa

II. Under him the uprisings developed into open

hostility. He had been sent to Palestine by the emperor at the request of a

deposed high priest (Jonathan), then living at Rome. Tacitus wrote of

Felix,

“In the spirit of a slave he carried out the

royal duties with all sorts of cruelty and lust” (Histories 5.9; cf. Acts

24:24-26; Josephus, Ant.

20.7, 2 § 142). The decades preceding his arrival

in Palestine saw the rise of Jewish “Zealots” (Gk zélütai, Aram

gannānāyê), chauvinists fanatically opposed to Roman occupation. Josephus

refers to them as “bandits” (lēstai) and records that

Felix

crucified countless numbers of them (JW

2.13, 2 § 253), in an effort to rid the country of them. A similar group,

the “Sicarii” (nationalists armed with short daggers, sicae, and dedicated to

the removal of their political opponents by quiet assassination, often at public

functions), also arose at this time. Political murders occurred almost daily;

their first victim was Jonathan the high priest, whom

Felix

was happy to have out of the way. There arose

still another group of villains, “with cleaner hands but more wicked intentions”

(JW 2.13, 4 § 258), who aroused the people to a wild enthusiasm against

Rome and claimed a divine mission. To this period probably belongs the exploit

of the Egyptian impostor of Acts 21:38. This Jewish false prophet led a crowd of

people to the Mt.

of Olives, promising that at his word the walls

of Jerusalem would fall so that they could enter the city and wrest it from the

Romans. Felix

went out to meet them with heavy-armed infantry;

the Egyptian escaped, but most of his force was either captured or killed.

During the last two years of

Felix’ procuratorship Paul lay in prison

at Caesarea (Acts 23:33-24:27). In the midst of

Felix’

term the Emperor Claudius died (13 October AD

S4), and Nero

succeeded him.

Nero

sent out Porcius Festus (ca. 60-62) to succeed

Felix;

he sincerely tried to be an honest administrator

(even showing favor to the Jews, cf. Acts 24:27). But the tinderbox situation

that had developed under Felix

was beyond the point of any lasting

solution. Soon after Festus’ arrival a dispute arose between the Jewish and

Syrian inhabitants of Caesarea; it was decided by an imperial rescript in favor

of the Syrians. This embittered the Jews still more. It was Festus who finally

sent Paul to Rome, when as a Roman citizen he used his right to appeal to the

emperor for justice (Acts 25:11fî.). The situation was not improved under the

next procurator L. Albinus (62-64), whose corruption was rampant. “There was no

form of crime that he failed to perform” (JW 2.14, 1§ 272).

|

FIRST

REVOLT

(66-70)

|

The last of the Roman procurators was Gessius

Florus (64-66), who by comparison made his predecessor seem to be a paragon of

virtue (JW 2.14, 2 § 277). He openly plundered the land, robbed

individuals, sacked towns, and took bribes from bandits. The Jews were greatly

humiliated in Caesarea when

Nero decided to grant the Gentiles

superior civic rights and the “Hellenes” obstructed access to the synagogue by

building shops before its entrance. They appealed to G. Florus, but he did

nothing to correct the situation. Later, when he took 17 talents from the Temple

treasury, the Jerusalem Jews could contain themselves no longer. With supreme

sarcasm and contempt they passed around their community a basket to take up a

collection for the “indigent” Florus (JW 2.14, 6 § 293fî.). He took

bloody revenge on them for the insult and turned part of the city over to his

soldiers for plunder. Since the priests tried to control the Jews during these

incidents and counseled them to patience, the meek attitude of the people, who

did not react against the soldiers, was interpreted by the latter as scorn.

Slaughter ensued. The Jews withdrew to the Temple precincts and soon cut off the

portico passageway between the Temple and the Fortress Antonia. Florus, who was

momentarily not strong enough to check the rebels, was forced to withdraw to

Caesarea. The revolt against Rome had become formal.

The

leader of the Jews was Eleazar, who was aided by Menahem, a son of the Zealot

leader Judas of Galilee. The land was organized for battle. The Sanhedrin

entrusted Galilee to the priest and Pharisee, Joseph, son of

Matthias

(= the historian Josephus; - Apocrypha, 68:114).

He was, however, suspected of disloyalty by John of Gischala, a leader of

Galilean Zealots; for Josephus spent more time in curbing the insurgents than in

organizing them. At first the Jews succeeded in routing the troops of G. Florus

and even those of C. Cestius Gallus, the legate of Syria, whose aid had been

summoned. Nero

eventually sent out an experienced field

commander, Vespasian, who began operations in Antioch in the winter of 66-67,

and soon moved against Galilee. Within a year the last of the Galilean posts

fell with the surrender of Josephus at Jotapata.

Northern

Palestine was once again subject to Rome. Two legions, the Fifth and the

Fifteenth, wintered at Caesarea (67-68), while the Tenth Legion was quartered at

Scythopolis (Beth-shan). Meanwhile, the Jews sought aid from Idumea, but the

Idumeans who came soon realized that the situation was hopeless and withdrew.

It seems that at this time the Jerusalem Christians fled to Perea, settling mostly in Pella (Eusebius, HE 3.5,

3). 160 In the spring of 68 Vespasian moved toward Jerusalem via

the Jordan Valley, seizing and burning rebel headquarters en route (Samaria,

Jericho,

Perea, Machaerus, Qumran, etc.). He would have

proceeded immediately to Jerusalem, had

Nero

not died on 9 June, 68. For this reason Vespasian

halted his activities and watched developments in Rome. Meanwhile, civil war

broke out in Jerusalem in the spring of 69.

Simon

bar Giora had been riding through the land with

bands, plundering what the Romans had left. Finally he turned toward Jerusalem,

where the people, tired of the tyranny of John of Gischala, welcomed the new

leader. John and his party withdrew to the Temple and closed themselves in,

while Simon

ruled in the city itself.

|

Siege of Jerusalem (69-70).

|

It was the Year of the Four Emperors:

Galba

succeeded

Nero

in Rome, but was murdered in January 69; Otho

then became emperor, but was soon replaced by Vitellius. The latter only

reigned until December 69. Since Vespasian had moved against Jerusalem in June

of 69 and the Roman troops acclaimed him imperator on

i

July, he soon returned to Rome, leaving his son

Titus to continue the attack on Jerusalem.

The

siege proper began in the spring of 70, just before Passover. Because the town

was accessible only from the N (deep valleys flanked it on the W, S, and E),

Titus encamped to the NE on Mt.

Scopus. At Passover riots took place

within the city in sight of the Romans, but the Jews eventually united to face

the common enemy. Titus then threw up circunivallation and in plain view of the

defenders crucified all who tried to flee from the besieged city. Hunger and

thirst began to tell, so that in July the Fortress Antonia was entered by the

Romans and razed. From this stronghold Titus was able to move toward the Temple.

Fire was set to the gates on the 8th of

Ab

(August) and entry was made on the next day. Titus wanted to spare the

Temple (JW 6.4, 3 § 241) but demanded surrender as the price. The people

refused; and when further fighting ensued on the loth, a soldier cast a blazing

brand into one of the Temple chambers. Although Titus tried to extinguish it,

confusion reigned and more firebrands were thrown. Before the Holy of Holies

was consumed, Titus and some of his officers managed to enter it to inspect it

(JW 6.4, 6-7 § 254). Roman standards were soon set up opposite the east

gate, and the soldiers “with the loudest of shouts acclaimed Titus imperator”

(JW 6.6, 1 § 316).

The

Jews were slaughtered. John of Gischala had withdrawn to Herod’s palace in the

upper city, and once more siege was set. By September 70 the city was finally

taken, plundered, and razed; its walls were torn down, with only a few sections

left standing. A Roman garrison was stationed in the city. John of Gischala,

Simon

bar Giora, and the 7-branched candlestick taken

from the Temple formed part of Titus’ triumphal procession at Rome in 711.

Pockets of rebels still had to be conquered throughout the land (at Herodium,

Masada, Machaerus); the last stronghold, Masada, did not yield until 74 (-

e. Apocrypha, 68:110).

Judaea

capta

was the inscription that appeared on the coins

struck for the Roman province thereafter. This inscription expressed a truth

with which the Jewish people have had to live until the formation of the modern

state of Israel. Except for a very brief time during the “Liberation of

Jerusalem” by Simon

ben Kosibah (Bar Cochba; - below), when it is

likely that the Temple sacrifice was resumed, the destruction of Jerusalem in AD

70 meant much more than the mere leveling of the holy city. It brought an end to

the tradition of centuries according to which sacrifice was offered to Yahweh

only in Jerusalem. This cultic act had made of Jerusalem the center of the world

for Jews. Now the Temple stood no more; Rome dominated the land as it had not

done before. The fall of Jerusalem represented a decisive break with the past.

From now on Judaism would emerge in a different direction. The Christian community was affected by this destruction too. To the Romans they

were subject people like the Jews; to the Jews they were traitors.

Christian refugees from Palestine carried to the Diaspora the reminiscences

of the life of Jesus and of Palestinian conditions that we find in the Gospels.

|

BETWEEN

THE

REVOLTS

(71-132)

|

After

Titus left Jerusalem in ruins, and a garrison was stationed there to maintain

Roman military control, the lot of the Jews was not easy. Roman colonists were

settled in Flavia Neapolis (modern Nablus) and 8oo veterans were given property

in Emmaus. In Jerusalem itself some of the old inhabitants, both Jews and

Christians, returned to live side by side with the Romans, as ossuaries and

tombs of the period attest. Vespasian claimed the entire land of Judea as his

private property, while tenant farmers worked the land for him.

The Jewish community, which was used to

paying a half-shekel as a tax for the Temple of Yahweh, now had to contribute

the same to the fiscus iudaicus for the Roman temple of Jupiter

Capitolinus. Religious practice shifted to certain forms of synagogue worship

and to a more intensive study of the Torah, which became henceforth the rallying

point for the Jews. With the destruction of the Temple the influence of the

Jerusalem Sanhedrin, headed by the high priest, waned. An academic Sanhedrin of

72 elders (or rabbis) in Janmia under the leadership of Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai

and later under Rabbi Gamalicl II took over the authoritative position in the

Jewish community. Even though Judea was ruled by the Romans, this Sanhedrin

enjoyed a certain autonomy. It fixed the calendar, and even functioned as a

court of law.

But

both in Palestine and in the Diaspora there was always a yearning for the

“restoration of Israel”-a yearning fed by the recollection of what had taken

place after the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC. While Trajan was occupied

toward the end of his reign with the threat of the Parthians, revolts of the

Jews occurred in various parts of the empire (Cyrene, Egypt, Cyprus,

Mesopotamia) ca. AD 1115-116. These uprisings stemmed in part from

oppression, but also from messianic expectations current among the Jews. The

general who finally put down the Mesopotamian revolt was a Romanized Moor,

Lusius Quietus, who was subsequently rewarded with the governorship of Judea.

This appointment, however, suggests that elements of unrest in that area called

for an experienced hand to manage the situation.

|

SECOND

REVOLT

(132-135).

|

The unsettled conditions in Judea

finally came to a head in the so-called Second Revolt. Its causes are not

certain. Dio Cassius (Rom.

Hist.

69.12, 1-2) records that it was sparked by

Hadrian’s attempt to build a Graeco-Roman city (Aelia Capitolina) on the site of

Jerusalem and to erect a shrine to Jupiter on the ruins of the Temple of Yahweh.

The Vita Hadriani 14.2 gives an imperial edict forbidding circumcision as

the cause for the revolt. Hadrian had previously prohibited castration, but

about this time renewed the prohibition and understood it to include

circumcision. Though the decree was not directed specifically against the Jews,

it affected them in a major religious issue. Both causes may be true.

At

any rate, the Jews rose up once again against the Romans. Coins struck by them

show that they regarded the uprising as the “Liberation of Jerusalem” and the

“Redemption of Israel.” Their intellectual leader was Rabbi Aqiba, their

spiritual leader, the priest Eleazar, and their military commander,

Simon

ben Kosibah (more commonly known by the name he

bears in Christian documents, Bar Cochba [Kochba, Cocheba]). Besides acting as

military commander, he administered the land politically from his headquarters,

probably in liberated Jerusalem. He preserved the elaborate administrative

machinery and division of Judea into toparchies that the Romans had set up.

Judea was now his private property, and tenant farmers paid their rent into his

treasury. His military tactics against the Romans were those of guerrilla

warfare, launched from many villages and outposts throughout the land (such as

Herodium, Tekoa, En-gedi, Mesad Hasidin [= Khirbet Qumran?], Beth-ter).

At

the beginning of the revolt the Roman governor, Tineius Rufus, was helpless,

even though he had Roman troops in the country. The legate of Syria, Publicius

Marcellus, came to his aid with additional troops, but eventually Hadrian was

forced to send his best general, Sextus

Julius

Severus, recalling him from Britain. Severus

succeeded in putting down the revolt, but only after a long process of starving

out the Jews who had taken refuge in strongholds and desert caves. In the

valleys of Murabba’at, Hever, and Se’elim, caves were used by families who fled

there with a few household belongings, biblical scrolls, and family archives.

Officers from En-gedi fled to the Hever caves, taking with them letters of their

commander, Simon

ben Kosibah.

When Jerusalem was once again captured by the Romans,

Simon

withdrew and made his last stand at Beth-ter

(near modern Bittir, about 6 mi. WSW ofJerusalem). The war reached its height

there in Hadrian’s 18th regnal year (134-135).

A siege was raised by the Romans, and Beth-ter finally fell.

Subsequently, Hadrian razed Jerusalem again, to build Aelia Capitolina. He

decreed “that the whole [Jewish] nation should be absolutely prevented from that

time on from entering even the district around Jerusalem, so that not even from

a distance could it see its ancestral home” (Eusebius, HE 4.6, 3).

The

defeat of the Jews in the Second Revolt [resulted in a diaspora that lasted]

1800 years. Until 1967 they were not to be masters of the ancient holy city and

the Temple area that had been for so many years the rallying point of the

nation. After the destruction of AD 70 the hope lived on that the city and the

Temple would be rebuilt. This hope was nurtured by the appearance of

Simon

ben Kosibah, who was even regarded as a messianic

figure (whence his name “Son of the Star” [bar Cochba; cf. NM 24:17], said to

have been given to him by Rabbi Aqiba). But it was an unfulfilled hope. He was

the last major Palestinian political leader whom the Jews had until modern

times. The hope of a return to Jerusalem and of a restoration of the Temple has

been a part of the prayer of the Jews ever since those early days (cf. the

prayer Shemoneh Esreh 14, 17).

Very

little is known about the Christian Church in Judea during this period. It was

certainly then that the clear break between the Synagogue and the Church took

place. When the Christians returned to Jerusalem after 70, the church there was

presided over by Simeon, the son of Clopas, who was bishop until his martyrdom

in 107. (Some would identify him with

Simon,

the “brother” of Jesus [Mk 6:3;

Mt

13:551,

so that a succes sion of Jesus’ relatives would

have ruled the Jerusalem church, in the manner of a “caliphate.” With less

evidence [Apostolic Constitutions 7.46], B. H. Streeter, The Primitive

Church [N.Y., 1929], identifies Judas or

Jude,

the “brother” of Jesus, as the third bishop of

Jerusalem.) After Simeon 13 other Jewish Christian bishops ruled the Jerusalem church up until the time of Hadrian

(i.e., up until 132 roughly): Justus, Zacchaeus,

Tobias,

Benjamin, John,

Matthias,

Philip,

Seneca,

Justus Levi, Éphraem, Joseph, and Judas

(Eusebius, HE 4.5, 3). Eusebius records that by the martyrdom of Simeon,

“many thousands of the circumcision came to believe in Christ” (HE 3.35). This suggests that there was an active missionary

program not only in the Diaspora but also in Judea itself.

|

THE

CLAUDIAN

DYNASTY

|

|

|

|

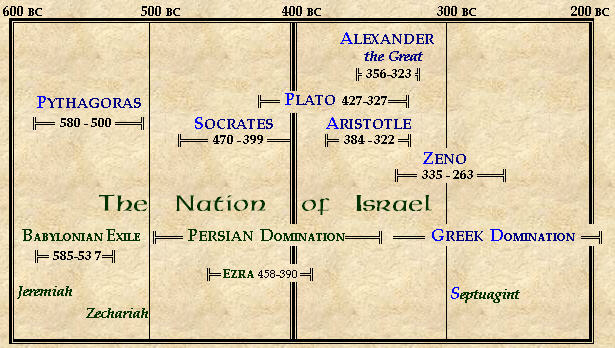

(2) [Timeline]

TIBERIUS

14-37

Punishes criticism of government:

encourages informants to denounce “traitors”. Initiates “police

state” and reign of terror.

|

|

|

(3) [Timeline]

CALIGULA

37-41

Demands that a statue of himself

be erected in the Temple in Jerusalem and accorded divine honors: dies

before the project is carried out.

|

|

|

(4) [Timeline]

CLAUDIUS

41-54

“Since

the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he

expelled them from Rome. . .”

|

|

“He

utterly abolished the cruel and inhuman religion of the Druids among the

Gauls, which under Augustus had merely been prohibited to Roman citizens;

on the other hand he even attempted to transfer the Eleusinian rites from

Attica to Rome, and had the temple of Venus Erycina in Sicily, which had

fallen to ruin through age, restored at the expense of the treasury of the

Roman people.”

Seutonius, Claudius, 25.

|

|

“ ...

Punishment

was inflicted on the Christians, a class of men given to a new and

mischievious superstition... ”

Suetonius, Nero 16 |

|

Tacitus, Annals xv. 44. But

all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the

propitiations of the gods did not banish the sinister belief that the

conflagration was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the

report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on

a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace.

Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty

during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius

Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition thus checked for the moment,

again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even

in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world

find their centre and become popular.

Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination when daylight had expired. Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. Hence, even for criminals who deserve extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man's cruelty, that they were being destroyed. |

|

|

(6) [Timeline]

VESPASIAN

69-79 Begins subjugation of rebellious Judea. |

|

(7) [Timeline]

TITUS

- 79-81 Completes subjugation of Judea. Destroys Temple in Jerusalem |

|

|

(8) [Timeline]

DOMITIAN

81-96 Demanded the titles and honor of a god while still living. Revived the spies and informers of Tiberias' era. |

|

Suetonius,

Domitian 12.17.

Besides other taxes, that on the Jews was levied with the utmost rigor,

and those were prosecuted who without publicly acknowledging that faith

yet lived as Jews, as well as those who concealed their origin and did not

pay the tribute levied upon their people.

|

|

|

κἀν τῷ αὐτῷ ἔτει ἄλλους τε πολλοὺς καὶ τὸν Φλάουιον <τὸν> Κλήμεντα

ὑπατεύοντα, καίπερ ἀνεψιὸν ὄντα καὶ γυναῖκα καὶ αὐτὴν συγγενῆ ἑαυτοῦ

Φλαουίαν Δομιτίλλαν ἔχοντα,

67.14.2

κατέσφαξεν ὁ Δομιτιανός. ἐπηνέχθη δὲ ἀμφοῖν ἔγκλημα

ἀθεότητος,

ὑφ' ἧς καὶ ἄλλοι ἐς τὰ τῶνἸουδαίων

ἤθη

ἐξοκέλλοντες πολλοὶ κατεδικάσθησαν, καὶ οἱ μὲν ἀπέθανον, οἱ δὲ τῶν γοῦν

οὐσιῶν ἐστερήθησαν· 67.14.3 ἡ δὲ Δομιτίλλα ὑπερωρίσθη

μόνον ἐς Πανδατερίαν. |

Cassius Dio

Roman History Epitome of Book 67:14,1-3 Greek: Historiae Romanae : Cassii Dionis Cocceiani historiarum Romanarum (Weidmann, Berlin pyr 1895-190. rpr. 1955)

14

… “And

the same year Domitian slew, along with many others, Flavius Clemens the

consul, although he was a cousin and had as his wife Flavia Domitilla, who

was also a relative of the emperor's. The charge brought against them both

was that of atheism, a

charge on which many others who drifted into Jewish

ways were condemned. Some of these were put to death, and the rest

were at least deprived of their property. Domitilla was merely banished to

Pandateria.”

|

|

THE

ANTONINES

(THE “FIVE Good Emperors”) |

|

|

(9) [Timeline]

NERVA

96-98 Dio Cassius says Nerva forbade accusations of maiestas (treason) or of “Jewish practice” |

|

|

(10) [Timeline]

TRAJAN

98-117 Pliny correspondence: Christians to be executed if obstinate, freed if recant. Not to be sought out |

|

|

(11) [Timeline]

HADRIAN

117-138 Christians are to be executed if won't recant; but false informants to be dealt with harshly. |

|

Ἀδριανοῦ ὑπὲρ Χριστιανῶν ἐπιστολή.

|

Epistle of {H}Adrian on Behalf of the Christians. |

|

Μινουκίῳ Φουνδανῷ.

68.6Ἐπιστολὴν

ἐδεξάμην γραφεῖσάν μοι ἀπὸ Σερηνίου Γρανιανοῦ, λαμπροτάτου ἀνδρός, ὅντινα σὺ

διεδέξω. 68.7 οὐ δοκεῖ οὖν μοι τὸ πρᾶγμα ἀζήτητον καταλιπεῖν, ἵνα

μήτε οἱ ἄνθρωποι ταράττωνται καὶ τοῖς συκοφάνταις χορηγία κακουργίας

παρασχεθῇ.

|

I have received the letter addressed to me by your predecessor Serenius Granianus, a most illustrious man; and this communication I am unwilling to pass over in silence, lest innocent persons be disturbed, and occasion be given to the informers for practising villany. |

|

68.10

εἴ τις οὖν κατηγορεῖ καὶ δείκνυσί τι παρὰ τοὺς νόμους πράττοντας, οὕτως

διόριζε κατὰ τὴν δύναμιν τοῦ ἁμαρτήματος· ὡς μὰ τὸνἩρακλέα, εἴ τις

συκοφαντίας χάριν τοῦτο προτείνοι, διαλάμβανε ὑπὲρ τῆς δεινότητος, καὶ

φρόντιζε ὅπως ἂν ἐκδικήσειας.

|

If, therefore, any one makes the accusation, and furnishes proof that the said men do anything contrary to the laws, you shall adjudge punishments in proportion to the offences. And this, by Hercules; you shall give special heed to, that if any man shall, through mere calumny, bring an accusation against any of these persons, you shall award to him more severe punishments in proportion to his wickedness. |

|

(12) [Timeline]

ANTONINUS

PIUS

138-161 |

|

|

(13)

MARCUS

AURELIUS

161-180 Authorizes amphitheater - torture by wild beasts for Christians in Gaul in 177 |

No comments:

Post a Comment