|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

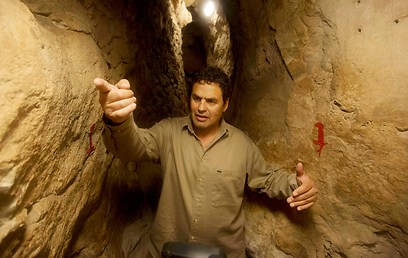

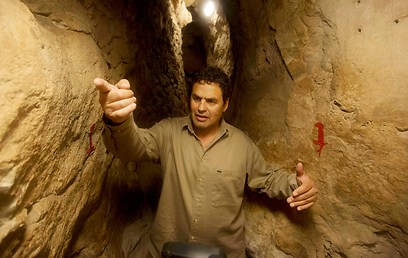

| Israeli archaeologist Eli Shukron Photo: AP |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Archaeologist claims to have found King David's Citadel

Skeptics question legitimacy of 'Bible archaeology' amidst rising concerns that digs escalate tension in eastern Jerusalem.

Associated Press

An Israeli

archaeologist says he has found the legendary citadel captured by King

David in his conquest of Jerusalem, rekindling a longstanding debate

about using the Bible as a field guide to identifying ancient ruins.

The claim by Eli Shukron, like many such claims in the field of

biblical archaeology, has run into criticism. It joins a string of

announcements by Israeli archaeologists saying they have unearthed

palaces of the legendary biblical king, who is revered in Jewish

religious tradition for establishing Jerusalem as its central holy city —

but who has long eluded historians looking for clear-cut evidence of

his existence and reign.

Israeli archaeologist Eli Shukron give a tour of what he claims to be King David's legendary citadel. (Photo: AP) Israeli archaeologist Eli Shukron give a tour of what he claims to be King David's legendary citadel. (Photo: AP)

The present-day Israeli-Palestinian conflict is also wrapped up in

the subject. The $10 million excavation, made accessible to tourists

last month, took place in an Arab neighborhood of Jerusalem and was

financed by an organization that settles Jews in guarded homes in Arab

areas of east Jerusalem in an attempt to prevent the city from being

divided. The Palestinians claim east Jerusalem, captured by Israel in

1967, as the capital of a future independent state.

Related Stories

Shukron, who excavated at the City of David archaeological site

for nearly two decades, says he believes strong evidence supports his

theory.

"This is the citadel of King David, this is the Citadel of Zion,

and this is what King David took from the Jebusites," said Shukron, who

said he recently left Israel's Antiquities Authority to work as a

lecturer and tour guide. "The whole site we can compare to the Bible

perfectly."

Most archaeologists in Israel do not dispute that King David was

a historical figure, and a written reference to the "House of David"

was found in an archaeological site in northern Israel. But

archaeologists are divided on identifying Davidic sites in Jerusalem,

which he is said to have made his capital.

Photo: AP Photo: AP

Shukron's dig, which began in 1995, uncovered a massive

fortification of five-ton stones stacked 21 feet (6 meters) wide.

Pottery shards helped date the fortification walls to be 3,800 years

old. They are the largest walls found in the region from before the time

of King Herod, the ambitious builder who expanded the Second Jewish

Temple complex in Jerusalem almost 2,100 years ago. The fortification

surrounded a water spring and is thought to have protected the ancient

city's water source.

The fortification was built 800 years before King David would

have captured it from its Jebusite rulers. Shukron says the biblical

story of David's conquest of Jerusalem provides clues that point to this

particular fortification as David's entry point into the city.

In the second Book of Samuel, David orders the capture of the

walled city by entering it through the water shaft. Shukron's excavation

uncovered a narrow shaft where spring water flowed into a carved pool,

thought to be where city inhabitants would gather to draw water. Excess

water would have flowed out of the walled city through another section

of the shaft Shukron said he discovered — where he believes the city was

penetrated.

Shukron says no other structure in the area of ancient Jerusalem

matches what David would have captured to take the city. The biblical

account names it the "Citadel of David" and the "Citadel of Zion."

Photo: AP Photo: AP

Ronny Reich, who was Shukron's collaborator at the site until

2008, disagrees with the theory. He said more broken pottery found from

the 10th century BC, presumably King David's reign, should have been

found if the fortification had been in use then.

Shukron said he only found two shards that date close to that

time. He believes the reason he didn't find more is because the site was

in continuous use and old pottery would have been cleared out by

David's successors. Much larger quantities of shards found at the site

date to about 100 years after King David's reign.

Reich said it was not possible to reach definitive conclusions

about biblical connections without more direct archaeological evidence.

"The connection between archaeology and the Bible has become very, very problematic in recent years," Reich said.

Critics say that some archaeologists are too eager to hold a

spade in one hand and a Bible in the other in a quest to verify the

biblical narrative — either due to religious beliefs or to prove the

Jewish people's historic ties to the land. But other respected Israeli

archaeologists say recent finds match the biblical account more than

naysayers claim.

Shukron, a veteran archaeologist who has excavated a number of

significant sites in Jerusalem, said he drew his conclusions after

nearly two decades exploring the ancient city.

"I know every little thing in the City of David. I didn't see in

any other place such a huge fortification as this," said Shukron.

The biblical connection to the site is emphasized at the City of

David archaeological park, where the "Spring Citadel" — the

excavation's official name — has been retrofitted for tourists,

including a movie projected on a screen in front of the fortification to

illustrate how it may have looked 3,800 years ago. The City of David —

located in east Jerusalem — is one of the most popular tourist sites in

the holy city, with 500,000 tourists visiting last year.

"We open the Bible and we see how the archaeology and the Bible

actually come together in this place," said Doron Spielman, vice

president of the nonprofit Elad Foundation, which oversees the

archaeological park. He carried a soft cover Bible in his hand as he

ambled around the excavation.

The site has come under criticism because of the Elad

Foundation's nationalistic agenda. Most of the foundation's funding

comes from private donations from Jews in the U.S. and U.K., and its

activities include purchasing Arab homes near the excavated areas and

then helping Jews move in, sometimes under heavy guard.

Critics say this political agenda should not mix with archaeology.

|

|

|

| 1. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. |

|

| yoni the Jew | , Jewish homeland | (05.07.14) |

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment