Time to engage

Barack Obama’s first-term caution was understandable, but he must now show greater resolve

To his supporters, this is far from all the president’s fault. Where Mr Obama has gambled to no obvious benefit—whether extending open hands to Iran and Russia, offering a cold shoulder to North Korea, or trying to heal the Middle East by reaching out to the Muslim world, for example—supporters blame the intransigence of other players. Where he has been cautious and slow to act—at the first dawning of the Arab spring two years ago, in Syria today—aides point to the lessons about the limits of American power learned over more than a decade of war. Serving and retired officials, policy experts and diplomats from friendly governments express understanding for the meagre results of Mr Obama’s first-term diplomacy. They see the logic of lowering ambitions and focusing sharply on that which can be achieved. They sympathise with his caution about confronting lobbies and special interests as he sought re-election. But if the president remains as coolly calculating and reluctant to engage in his second term, even firm friends will find it hard to forgive.

Mr Obama’s first months in office were a time of vaulting ambition. There were hopes he might heal the world as he had seemed to heal racial and partisan divides at home. They were soon dashed. Since then a tone of cool detachment has been his foreign-policy hallmark. From being the “indispensable nation”, Mr Obama’s America seeks to be an indispensable catalyst: present, but not deeply involved.

The darkest evening

Thus America has sought to create the conditions for success—as in

hotspots like Libya—while resolutely avoiding deeper entanglements.

Anne-Marie Slaughter, director of policy planning at the State

Department during Mr Obama’s first two years, talks of a global order in

which America offers “tough love” while pressing rising powers to share

the burden.The response to the bloodshed unleashed by Syria’s rulers against its people shows the difficulties of this approach; if you can’t find a desired outcome to catalyse, what do you do? The response of doing nothing leaves the administration’s inner circles miserable. Mr Obama has heard appeals to arm rebel groups, to impose a no-fly zone on Syria or take out the despot’s air forces on the ground. His response is to ask for evidence that such interventions would make things better, rather than satisfy the urge to “do something” at the risk of escalating the conflict. His second response is to ask for the price-tag: no small matter to a nation tired of war. Internal arguments have been passionate. Whom would you have us bomb, administration doves ask more hawkish types: snipers in cities? How much American power, they demand to know, would be needed to bring peace? After all, almost 150,000 American troops were in Iraq at the peak of its sectarian killings. So America is left rallying support for the formation of an inclusive opposition and preparing for the day after the Assad regime falls. The reluctance to act, says a witness to the debate, is understandable. It is also, he adds, a “shame on all of us”.

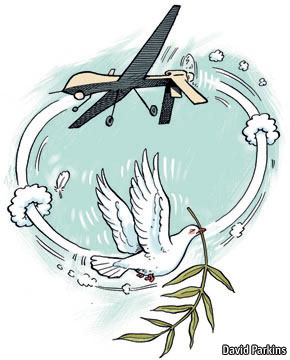

Both critics of Mr Obama and many of his admirers would like to see greater engagement and resolve across three broad categories of endeavour. First come fast- and slow-burning crises that cannot be ignored, from the Middle East to North Korea. There is business from the first term—notably the withdrawal from Afghanistan—which could add to that sad roll-call if bungled. Second, there are opportunities too important to be shunned, from deepening free trade with Europe to the century-defining task of persuading China that its self-interest lies in an international order based on rules. And finally there are duties, often stemming from promises Mr Obama made when he first came to power, which have until now been shirked. Those include slashing nuclear stockpiles and writing rules for warfare in the 21st century that are worthy of America, a nation built on the supremacy of the law.

Important countries and regions are glaringly absent from the “to-do” lists circulating in official Washington and its more influential think-tanks. This reflects both a realistic sense of the limits on presidential time and attention, and brutal assessments of domestic American politics. A Presidential Briefing Book from the well-connected Brookings Institution does not include a serious push on climate change (a key European wish) in its list of “Big Bets” for second-term action. It urges an easing of the Cuba embargo, but rising powers such as Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey feature mostly as sources of anxiety, with Mr Obama urged to work on keeping them aligned with a liberal, democratic world order.

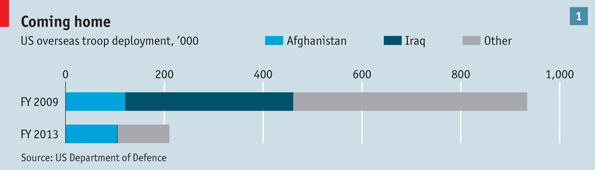

Mr Obama’s choice of war-wary Vietnam veterans to head his foreign policy team, with John Kerry slated to run the State Department and Chuck Hagel, more controversially, the Pentagon, signals an intent to pursue diplomatic solutions to security crises, and to complete the winding-up of George W. Bush’s military campaigns (see chart 1). Mr Hagel, a former Republican senator who became a sceptic of the Iraq war, will have to work hard for his Senate confirmation: conservatives allege that he is insufficiently pro-Israel. Yet war-weariness in the electorate has left Republicans struggling to find lines of attack against Mr Obama’s overseas policies. A standing charge that Mr Obama feels the need to apologise for American greatness and a complex spat about the murder of America’s ambassador to Libya have both felt slightly forced. Most conservatives would rather talk about “the Latino vote, women’s votes and the soul of the Republican Party” than foreign policy, sighs a think-tank boss.

When it comes to crisis-management, Mr Obama did set some clear triggers for military action in his first term. He has declared the use of chemical weapons to be a red line the Syrian regime cannot cross. Though some on the right are sceptical, sources say he has committed himself irrevocably to preventing Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon, notably in a speech to pro-Israel activists in March 2012.

Miles to go

Iran has been, so far, the perfect example of an area where Mr

Obama’s policy has been sober, realistic and hard to fault, but has

produced slender results. One rather bleak achievement stands out.

During the presidency of George W. Bush, Europe, China and Russia all

assumed that Washington was to blame for bad Iranian-American relations,

says Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran expert with the Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace, a think-tank. When Mr Obama’s offered hand of

friendship was knocked away, he at least demonstrated that Iranian

intransigence was to blame—and that opposing America is one of the only

ways in which the Iranian regime maintains legitimacy in the eyes of its

supporters. That finding allowed America to rally international support

for unprecedented economic sanctions, but exposed how hard the crisis

is to solve.In the long run Ali Khamanei, Iran’s supreme leader, faces two logical choices. He could make a deal in which Iran keeps a face-saving limited capacity for nuclear enrichment, subject to intrusive international inspections: he could risk a sprint to “become Pakistan” with a nuclear-weapons fait accompli. The first is unappealing, the second risky, giving him cause to play for time. In recent months Iran has signalled a willingness to buy time by diverting some of its stockpile of 20%-enriched uranium into fuel for a small research reactor in Tehran used to produce medical isotopes. Add international inspections to that mix, plus curbs on other uranium enrichment, and optimists think an imperfect interim deal could take shape, capable of postponing a larger nuclear stand-off. American sources are less cheerful, saying the crisis remains stuck in a murky status quo.

In 2012, beribboned American generals suggested that Israel does not have the ability to strike Iran alone, lacking the most powerful and precise munitions to penetrate Iranian bunkers; but some in Mr Obama’s government concede that Israel has a military option, even if it is not as good as America’s. Israel is effective at placing pressure on America, via Congress. But neither Congress nor Israel’s prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, can make Mr Obama launch a war he does not want. Senator Kerry’s nomination underscores Mr Obama’s belief that America must pursue diplomacy to the bitter end, and be seen to do so, sources say. That does not mean it will work, they add, with heartfelt gloom.

The situation in the wider Middle East does little to lighten their mood. Mr Obama took office hoping that by pairing unprecedented security co-operation with Israel and public outreach to the Muslim world he could prepare the ground for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He was wrong. Mr Obama lost Israeli public opinion, failed to gain Muslim trust, and was humiliated by the open defiance of an Israeli prime minister. In a move not reported at the time, sources say that Hillary Clinton, the outgoing secretary of state, pushed Mr Obama two years ago to go over the heads of the region’s leaders and lay out the shape of a two-state peace deal to the Israeli and Palestinian people. The White House declined; it remains unwilling to “seize history”, in the frustrated words of one source.

Dark and deep

Mr Obama’s image in Israel may have improved. Unhappy at his failure

to visit their country as president, Israelis were sincerely grateful

for his political backing for their right to self-defence, and for help

with the Iron Dome missile-defence system, as rockets rained in from

Gaza late last year. Yet more cautious supporters of the president scoff

at suggestions that an Obama speech exists that could inspire Israelis

to demand a peace deal their elected government does not want. This

cautious camp concedes that most Israeli voters say they favour a

two-state solution, but points to predictions that another, severely

conservative Israeli government will be elected on January 22nd (see article). Deep down, say the sceptics, Israelis doubt that Palestinian leaders can deliver peace.Mr Kerry, though, favours fresh initiatives. And insiders talk of three changes that could give America greater leverage. One is Israel’s growing diplomatic isolation. In the recent UN vote on the status of Palestine the Czech Republic was Mr Netanyahu’s only European ally. The second change would be an Iran crisis ending in an American strike. For the sake of Muslim opinion, Mr Obama would need hefty Israeli concessions on such issues as settlement-building, and should be able to demand them. A third would be triggered by a collapse of the Palestinian Authority and an uprising on the West Bank.

The Middle East is not the only place to see a scaling back of ambitions. When the Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, was in Washington on January 11th, Mr Obama sketched out plans for a “very limited mission” for American forces in the country after 2014. Some White House aides are said to be pushing for a garrison of as few as 2,500 troops, far smaller than was discussed only a year ago. Mr Obama asserted that America had achieved its central goal: to dismantle al-Qaeda and prevent Afghanistan from being used as a future launch pad for attacks against America. Had years in Afghanistan achieved everything some had imagined possible? he asked rhetorically. Probably not, was his cool response. But in human enterprises, “you know, you fall short of the ideal.” America continues to launch drone strikes in Pakistan. But the largest battlefield of the “war on terror”, Iraq, is mentioned now mostly in the context of America’s lack of influence there. In December 2012 American officials went public with their anger at Iranian shipments of arms to Syria through Iraqi airspace. Iraq brushed off the charge, and the American public responded with a collective shrug.

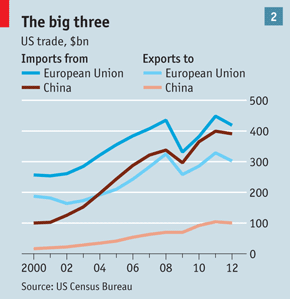

The keystone of the president’s diplomacy was and is the “pivot” to Asia. The challenge is to steer a course between engagement with a rising China and demands from China’s neighbours for America to play a balancing role in the region. This is made trickier because American relations with China are saddled with a split personality.

A reasonably pragmatic, modernising China is mostly willing to discuss global issues, from rules for trade to action on climate change to diplomatic help with Iran or the Arab spring. America’s offer is straightforward: play by global rules, show restraint in the neighbourhood and we will not prevent you becoming the world’s largest economy. Yet where regional issues, such as territorial spats in the seas off China (see article) are involved, an older, pricklier China prevails, convinced that America is bent on containing its rise both directly and by stirring up smaller neighbours and regional powers.

It is particularly troublesome that North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, which America sees as a question of global security, fall for China into the second category of touchy, quasi-domestic concerns. America tells China that the longer North Korea remains a threat, the longer America will have to maintain hefty military forces in China’s back yard. But China’s fears of a North Korean collapse run deeper, leaving it unwilling to press the regime too hard.

The election of a Japanese government willing to invest more in defence fulfils a long-standing American wish, but sparks new worries that islets and scraps of territory could incite regional clashes. American ties with India have deepened dramatically in recent years. But in the absence of fresh initiatives, or tangible results from old ones, experts talk of “India fatigue” in Washington.

Even supporters of a balanced Asia policy fret that the Chinese part of the relationship needs shoring up, urging Mr Obama to engage swiftly and closely with the new leader, Xi Jinping, and to work on dangerously threadbare ties between the two countries’ armed forces.

Economic relations offer more promise. Mr Obama has held back from visible trade spats which might spook the market, instead pushing his team to find discreet ways to retaliate against such Chinese bad behaviour as the theft or forced transfer of Western technology, or market-distorting subsidies. As well as these sticks, America also has carrots. China is increasingly eager to invest abroad, which gives it new reason to play by international rules. Negotiations around the Trans Pacific Partnership, a trade pact that currently excludes China, could also offer inducements.

Promises to keep

Political calculations help explain the catalogue of grand promises made and then shirked during Mr Obama’s first term. The second term may see more progress on nuclear disarmament, including a push for fresh talks with Russia, though relations with Vladimir Putin are in dreadful shape. The Syrian crisis offers fresh evidence of dire relations. Intense American attempts to convince Mr Putin that cold self-interest should lead him to ditch the Assad regime have led nowhere. A senior figure questions the conventional wisdom that Russia is protecting a Middle Eastern ally, suggesting that Russia is really concerned about denying America leadership of a new world order involving humanitarian interventions. Mr Putin would rather see Syria descend into a “mess of slaughter” than see America get what it wants.

Russia’s president is expected to link any bid to discuss disarmament to American plans for missile-defence systems deployed in Europe, which are aimed at Iran but which Russian generals present as a bid to neutralise their nukes. If Russia will not talk, Mr Obama may look at cutting American arsenals unilaterally.

On climate change—a passion of Mr Kerry’s—America places few hopes in the cumbersome UN process. Bilateral and multilateral deals with other big emitters of greenhouse gases might be possible, not just on carbon emissions but also on pollutants with shorter-term warming effects. But the domestic politics would have to change for Mr Obama to be able to make substantive offers to, say, China.

Mr Obama always planned for an eight-year presidency. The first half was for laying groundwork, not getting results. Maybe, but such excuses will not wash for four more years.

No comments:

Post a Comment