Declassified Documents and the B-53 Bunker Buster

October 21, 2010

Walter Pincus’s Washington Post article, “Story of B-53 ‘bunker buster’ is a lesson in managing nuclear weapons,”

provides a fascinating look at the arcane and highly secret history of

U.S. nuclear weapons planning. Pincus shows that the highly dangerous,

massively destructive B-53 stayed in the nuclear arsenal for decades

because of its mission: the destruction of underground bunkers.

Weapons designers concocted the B-53 after U.S. intelligence had

identified the underground installations that would house Soviet leaders

in time of superpower crisis and war. Yet the B-53 was so dangerous

that practice loading of them on B-52 bombers was forbidden. If a

substantial quantity of B-53 had been used in war, their radioactive

fallout would have caused worldwide environmental damage. Production of

some 300 B-53s began in 1962, but by the end of the Cold War the

Pentagon kept only 50 in the active stockpile. They were not retired

until the late 1990s when a replacement, the B-61-11, came on line.

Until recently the B-53s could not even be disassembled like other

retired weapons; Washington had no plan for safely disaggregating the

dangerous chemicals and highly-enriched uranium in the weapon’s core.

Such problems informed Pincus’s lesson: “Don’t build more weapons than

you need or could use.”

Mr. Pincus noted that a retired senior military officer was one of his sources. Interview sources are essential, because the story of high yield weapons in the U.S. nuclear arsenals is not an easy one to tell using declassified documents. A heavily excised Defense Department memorandum makes the point. It is from Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance to President Lyndon B. Johnson, dated 10 April 1964 on “High yield nuclear weapons.” The previous year, President Kennedy had asked federal agencies to investigate the possibility of developing a “very high yield nuclear weapon.” The proposed explosive yield of the projected “very high yield” weapon is excised, but it was probably substantially higher than the 9 megaton B-53, perhaps in the order of 15 or 20 megatons (or more). Vance may have been referring to the B-53 when he discussed which weapons–or how many–could be used for attacking “very hard targets,” and that an unspecified high yield weapon would “offer only a slight margin of superiority” over the equivalent unspecified weapon type. The numerous excisions make it difficult to grasp the argument. Vance recommended against the development of very high yield weapons, but in the event that the Limited Test Ban (1963) broke down, he endorsed preparations for atmospheric testing of high yield weapons as a way for scientists to draw conclusions about the effects of weapons with even higher yields.

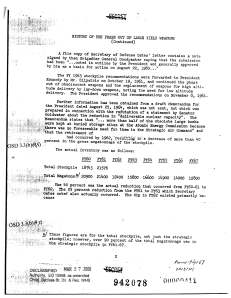

Another excised document, a Defense Department briefing paper from September 1967, “History of the Phase Out of Large Yield Weapons,” provides some prehistory for the B-53. The Mk-36 was an earlier massive nuclear weapon, weighing over 8 tons and with the same 9 megaton yield as the B-53 (which weighed about 5 tons). [i] The Mk-36 accounted for a huge share, some 40 percent, of the total explosive yield of the nuclear weapons stockpile during the late 1950s. Unlike the B-53, however, the Mk-36 may have been a general purpose weapon, not slated for a specific mission. By the end of the 1950s, U.S. defense planners believed that the nuclear arsenal needed larger numbers of a relatively smaller weapon, with a yield in the one megaton range (possibly the B-43). Such weapons would be more appropriate for target planning because they could be used for “multiple loading, highly selective and low altitude bombing.” Consequently, President Eisenhower and Secretary of Defense Thomas Gates approved plans to phase out the B-36, which finally occurred during Fiscal Year 1962. As the table on page 2 shows, from FY61 to FY62 total megatonnage for all U.S. nuclear weapons dropped from a high of 21,400 to 12,400, a huge decrease. The introduction of the high yield B-53 may partly explain the uptick in the following fiscal years, but not the drop to significantly lower megatonnage numbers during FY 1965-1967.

Excessive secrecy accounts for the significant excisions from these documents. The source for the Vance memorandum is obscure and it is unclear which exemptions the Pentagon invoked to withhold data from it. It was classified under the Atomic Energy Act so it is possible that the Pentagon used the rules for “Formerly Restricted Data” to withhold some of the information. Important classes of nuclear secrets (e.g., weapons design or technology for producing fissile material) are worth protecting, but it is unlikely that the information withheld from Vance’s memorandum would help a would-be profliferant. From the document on the “Phase Out of Large Yield Weapons,” the size of the Mk-36 force is sanitized as is the explanation for the “dip in FY62.” The Defense Department justified the excisions on the grounds that the information related to war plans “still in effect” and that the information would “impair the application of state of the art technology within a U.S. weapon system.” Of course, neither of those exemptions seems plausible. The document is under appeal at the Information Security Classification Appeals Panel.

Perhaps if secrecy had not protected the B-53’s checkered history for so many years, public pressure might have led to a far earlier retirement for such a dubious weapon system.

Mr. Pincus noted that a retired senior military officer was one of his sources. Interview sources are essential, because the story of high yield weapons in the U.S. nuclear arsenals is not an easy one to tell using declassified documents. A heavily excised Defense Department memorandum makes the point. It is from Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance to President Lyndon B. Johnson, dated 10 April 1964 on “High yield nuclear weapons.” The previous year, President Kennedy had asked federal agencies to investigate the possibility of developing a “very high yield nuclear weapon.” The proposed explosive yield of the projected “very high yield” weapon is excised, but it was probably substantially higher than the 9 megaton B-53, perhaps in the order of 15 or 20 megatons (or more). Vance may have been referring to the B-53 when he discussed which weapons–or how many–could be used for attacking “very hard targets,” and that an unspecified high yield weapon would “offer only a slight margin of superiority” over the equivalent unspecified weapon type. The numerous excisions make it difficult to grasp the argument. Vance recommended against the development of very high yield weapons, but in the event that the Limited Test Ban (1963) broke down, he endorsed preparations for atmospheric testing of high yield weapons as a way for scientists to draw conclusions about the effects of weapons with even higher yields.

Another excised document, a Defense Department briefing paper from September 1967, “History of the Phase Out of Large Yield Weapons,” provides some prehistory for the B-53. The Mk-36 was an earlier massive nuclear weapon, weighing over 8 tons and with the same 9 megaton yield as the B-53 (which weighed about 5 tons). [i] The Mk-36 accounted for a huge share, some 40 percent, of the total explosive yield of the nuclear weapons stockpile during the late 1950s. Unlike the B-53, however, the Mk-36 may have been a general purpose weapon, not slated for a specific mission. By the end of the 1950s, U.S. defense planners believed that the nuclear arsenal needed larger numbers of a relatively smaller weapon, with a yield in the one megaton range (possibly the B-43). Such weapons would be more appropriate for target planning because they could be used for “multiple loading, highly selective and low altitude bombing.” Consequently, President Eisenhower and Secretary of Defense Thomas Gates approved plans to phase out the B-36, which finally occurred during Fiscal Year 1962. As the table on page 2 shows, from FY61 to FY62 total megatonnage for all U.S. nuclear weapons dropped from a high of 21,400 to 12,400, a huge decrease. The introduction of the high yield B-53 may partly explain the uptick in the following fiscal years, but not the drop to significantly lower megatonnage numbers during FY 1965-1967.

Excessive secrecy accounts for the significant excisions from these documents. The source for the Vance memorandum is obscure and it is unclear which exemptions the Pentagon invoked to withhold data from it. It was classified under the Atomic Energy Act so it is possible that the Pentagon used the rules for “Formerly Restricted Data” to withhold some of the information. Important classes of nuclear secrets (e.g., weapons design or technology for producing fissile material) are worth protecting, but it is unlikely that the information withheld from Vance’s memorandum would help a would-be profliferant. From the document on the “Phase Out of Large Yield Weapons,” the size of the Mk-36 force is sanitized as is the explanation for the “dip in FY62.” The Defense Department justified the excisions on the grounds that the information related to war plans “still in effect” and that the information would “impair the application of state of the art technology within a U.S. weapon system.” Of course, neither of those exemptions seems plausible. The document is under appeal at the Information Security Classification Appeals Panel.

Perhaps if secrecy had not protected the B-53’s checkered history for so many years, public pressure might have led to a far earlier retirement for such a dubious weapon system.

[i]

The predecessors of the B-36 had an even great yield. The Mk-17

(B-17)’s, was between 10 and 15 megatons as was the B-24’s. Both were in

the arsenal during the 1950s for only a few years. See Stephen I.

Schwarz, ed., Atomic Audit: The Cost and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Since 1940 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1998), 86-87.

No comments:

Post a Comment